Share

Anil Aggrawal's Internet Journal of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology

Volume 26 Number 2 (July - December 2025)

Received: Jan 25, 2025;

Revised: manuscript received; May 22, 2025

Accepted: June 18, 2025

Published: June 18, 2025

Ref: Mukesh R, Toi PC , Chaudhari VA, Pandiyan KS, Kumaran M. Death due to Clinically Undiagnosed Hematolymphoid Malignancy: An Autopsy Case Report and Review. Anil Aggrawal's Internet Journal of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology [serial online], 2025 ; Vol. 26, No. 2 (July - December 2025): [about 16 p].

Available from: https://www.anilaggrawal.com/ij/vol-026-no-002/papers/paper002

Email: mukeshfmt22@gmail.com

( All photos can be enlarged on this webpage by clicking on them )

Death due to Clinically Undiagnosed Hematolymphoid Malignancy: An Autopsy Case Report and Review

Abstract

B-cell lymphomas, a type of hematolymphoid malignancy, constitute 90% of all lymphomas. We report an autopsy of a 33-year-old male with a clinical history of hypothyroidism and anemia brought unresponsive to casualty. The body exhibited no external injuries. Sparse and fine hairs were present in the face, chest, axilla and pubic region, with reduced right testicular size and scrotal volume. The thyroid gland was grossly not palpable and internally untraceable. The spleen was enlarged and softened with a wedge-shaped infarct in the cortical region and a hilar abscess. Under microscopy, the liver showed periportal chronic inflammation, bridging fibrosis and focal interface hepatitis. Acute tubular necrosis with thyroidization of tubules and focal tubular atrophy was reported in the kidney. Lymphoid infiltrates were found in the testis, brain parenchyma, pituitary, and liver, positive for markers like Tdt (Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase), CD34, and CD79a. The cause of death was opined as acute tubular necrosis due to septicemia secondary to B-cell lymphoma. After tissue or organ infiltrations, B-cell lymphomas are frequently linked with immunosuppression and multiorgan dysfunction, leading to death. Postmortem immunohistochemistry has helped in finding the key diagnosis in this case. In cases of unexplained anemia or endocrinological abnormalities, autopsy surgeons should rule out hematolymphoid malignancy. Clinicians must include the workup for hematolymphoid diseases in cases with atypical presentation.

Keywords-

B cell lymphoma; Splenic infarction; Thyroidization; Immunohistochemistry in lymphoma; Hypothyroidism; Thyroid Dysgenesis; life threatening anemia

Glossary

Bcl: B-cell lymphoma, a general term for lymphomas affecting B cells.

● CD: Cluster of Differentiation, a system used to classify different types of white blood cells. It was suggested in 1982.

● CD34 – CD 34 is a cell surface protein that is commonly used as a marker to identify hematopoietic stem cells (the cells that give rise to all other blood cells) and endothelial cells.

● Clone QBEnd/10 -A specific monoclonal antibody that targets the CD34 protein. Q is a designation given by the laboratory or company that developed the antibody.

BEnd: indicate the target [end part refers to endothelial cells]. CD34 is commonly used to identify endothelial cells. 10 represents a sequential identifier, indicating that this is the 10 th clone developed in a series.

● DIC - Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation

● DLBCL: Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma, a common type of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma.

● ECG: Electrocardiogram

● HLM: Hematolymphoid Malignancy

● IVBCL: Intermediate-grade B-cell Lymphoma, another type of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma.

● Ki: Ki-67, a protein marker used to assess cell proliferation.

● MUM-1: Multiple Myeloma 1. It plays a role in the differentiation of B-cells into plasma cells. It is often used as a marker in immunohistochemistry to identify certain types of lymphomas and myelomas

● NHL: Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, a type of cancer affecting the lymphatic system.

● PAX: PAX genes - a family of genes involved in the development

● RBC- Red Blood Cells

● Tdt: Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase, an enzyme involved in DNA synthesis. It is a specialized DNA polymerase. TdT is primarily expressed in immature, pre-B, and pre-T lymphoid cells, as well as in acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma cells

● Thyroidization - Thyroid like appearance in renal tissue

Introduction

Natural deaths due to disease and senility may be unexplained, where the cause of death is not known or unclear to the treating physician[1,2]. "Sudden unexplained death" refers to an unexpected and sudden death in an individual older than 1 year [3]. Unexplained sudden death (Intrinsic Factor(s) Identified) is a type of cause of death statement when the causality of death can be determined. However, intrinsic natural abnormalities like known intrinsic risk factors for sudden death or those of unknown significance are present. Trauma and other unnatural etiologies are properly excluded in such cases [4,5]. In a study, about 6-12% of cases subjected to medicolegal autopsies were determined to have died of natural causes [6]. About 35% of brought dead cases were reported to have a natural cause of death at autopsy [7]. About 8% of adult cases revealed clinically undiagnosed malignancy in autopsy [8]. About 20% of the clinically unsuspected malignancy was detected at the time of autopsy, while 16% presented with metastasis. Among the autopsy-diagnosed cancers, the primary cause of death was malignancy in 16% of such cases, which also includes hematolymphoid malignancies [9].

Hematolymphoid malignancies (HLM) are primary cancers affecting blood, bone marrow, and lymphoid organs, originating from either myeloid or lymphoid cell lines. Lymphomas, lymphocytic leukemia, myelomas and other plasma cell dyscrasias arise from lymphoid cell lines. In contrast, acute myeloid leukemia (AML), chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and other myeloproliferative disorders (MPD) are myeloid in origin. Immunohistochemical markers like CD1a(Cluster of Differentiation 1a), CD3 (Cluster of Differentiation - 3), CD7 (Cluster of Differentiation 7), CD8(Cluster of Differentiation 8), CD20 Cluster of Differentiation 20), CD30 (Cluster of Differentiation 30), CD 34 (Cluster of Differentiation - 34), CD 79a (Cluster of Differentiation -79a), TdT (Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase), MIB (Cell Proliferation Marker), LCA (Leucocyte Common Antigen), etc. are used in the biopsy diagnosis of various types of HLMs with their expressivity in staining. Organ infiltration from leukemia, lymphoma, myeloma, and related conditions is less likely to be symptomatic than from carcinoma. Patients with HLM are at risk of complications from the neoplasm and treatment [10]. We present an autopsy case report with a postmortem diagnosis of lymphoma in the deceased, who was brought dead to casualty in our hospital after a brief period of hospitalization in another health care center.

Case Report

We conducted an autopsy of a moderately built 33-year-old man. The deceased allegedly had anemia and hypothyroidism and was suffering epigastric pain along with reduced urine output for 3 days prior to death. As per the clinical records, prior to death, he was admitted to a hospital for management for 13 days. The lab values during the admission period were as follows: Hb-4.5g%, WBC- 12800/mm3, Neutrophils - 67%, Lymphocytes - 29%, Eosinophils - 4%. T3- 46.96 ng/dl (Normal- 70-204 ng/dl)), T4- 2.6 microgram/dl (Normal- 4.6-10.5 microgram/dl), TSH - 1.76 microIU/ml (normal - 0.4 - 4.2 microIU/ml), Blood urea - 40 mg/dl, Serum Creatinine- 1.2 mg/dl, Blood sugar - 87 mg%. ECG showed T wave inversion in V1-V3. The treatment included diuretics, iron supplementation, packed RBC transfusion, antibiotic prophylaxis, and thyroxine supplementation.

On external general examination, the body had no injuries, measuring 165 cm in length and 55 kg in weight. The conjunctiva was pale, while fingernails and toenails had nail paint. Natural orifices were free without any discharges. Sparse and fine hairs were present in the face, chest, axilla and pubic region (Figure 1A, 1B, 1C). The volume of the scrotum appeared relatively reduced (Figure 1C).

On internal exploration, the thyroid was not traceable in the anatomical or reported ectopic locations. In front of the arch of the aorta above the tracheal bifurcation, there was a solid grey-white mass measuring 1.5cm X 0.8cm X 0.8cm situated in the superior mediastinum. The adjacent muscle tissue was flabby and more softened. The spleen was soft with an intact capsule measuring 18cm X 11cm in frontal view and 750 g in weight. The cortex showed a coalesced pale infarct involving the entire organ and a wedge-shaped advanced infarct (Figure 2A). A splenic abscess measuring 3cm X3 cm had developed in the hilar region. Liver was congested with intact capsule. Lungs were congested and edematous (Figure 2B). Most segments were firm in consistency. There were multiple petechial hemorrhages in the right atrium and at the base of great vessels, and coronaries were patent. Examination of the kidneys revealed fatty infiltration with renal pelvis hemorrhage (Figure 2C). The right testis was smaller, measuring 4cm X 2cm X 2cm. Left testis appeared grossly normal. The thoracic cavity contained straw-brown colored fluid estimated to be about 750ml (Figure 2D).

In Figure-2

2A Infected pleural fluid in thoracic cavity (Arrows)

2B Frothy edematous fluid in lungs & trachea (Arrow Heads)

2C Infarcts in spleen (asterisk - advanced)

2D Infarcts (Asterisk) & hemorrhagic extravasation with necrosis (arrow head) in kidney

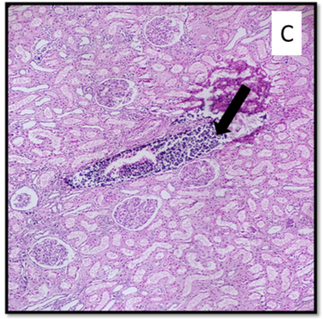

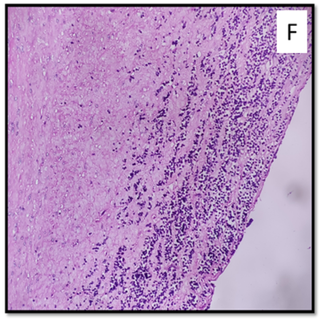

Under microscopy, the lungs showed dilated alveoli with interstitial congestion, chronic inflammatory cells with bacterial clumps, and hemosiderin macrophages. The liver showed chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and sinusoidal dilatation with lymphoid cells. The testes showed atrophy of seminiferous tubules and immature lymphoid cells in the interstitium with thickened tunica (Figure 3A). The thymus showed hyperplasia and thick-walled vessels (Figure 3B). Kidney tubules showed acute tubular necrosis, thyroidization, and atrophy with tubular hyaline casts (Figure 3C). Tonsil showed increased lymphoid cells, while lymph nodes showed reactive changes (Figure 3D). The brain showed dilated vessels filled with lymphocytes and parenchymal lymphocytic infiltrates (Figure 3E). The pituitary showed diffuse infiltration of immature lymphoid cells, highlighted with CD79a. The left ventricle showed pericardial fat with chronic inflammation, interstitial oedema, and lymphoid aggregates. The right ventricle of the heart showed thick- walled vessels and lymphoid aggregates. The aorta shows atherosclerotic changes along with lymphoid aggregates (Figure 3F). The unidentified thick mediastinal mass from the thorax showed interstitial spaces and lymphoid aggregates in the background of skeletal muscle cells. The suitable tissues were subjected to immunohistochemistry.

Fig 3. Microscopic examination (Hematoxylin & Eosin) showing lymphoid infiltrates in various oegans:

A- Testis (10x)

B- Thymus (40x)

C- Kidney (10x)

D- Tonsil (4x)

E- Brain (40x)

F- Aortic wall (4x)

Immunohistochemical staining with primary and secondary antibodies (PathnSitu Biotechnologies) was performed using Ventana platform for CD3 (clone Polyclonal), CD20 (clone L26), CD34 (clone QBEnd/10), CD79a (clone HM47) and TdT (Polyclonal Rabbit Anti-Human TdT Antibody (Abcam, Cat# ab19515)) in a dilution of 1:200 with standard operating protocol. The moderate intensity of DAB chromogen in the slide image was considered positive expressivity. On immunohistochemistry, Tdt, CD34, and CD79a highlighted the immature (probably blast) cells in the pituitary, liver and testis. CD3 and CD20 were negative in the immature B cells. Hence, the possibility of B cell leukemia or lymphoma was reported from histopathological impressions. Blood and sterile fluid culture showed the growth of Escherichia coli. Toxicological examination did not detect any poison or drugs in this case. The cause of death was opined as acute tubular necrosis due to septicemia as a complication of B cell lymphoma.

Discussion

More than 30% of HLM cases diagnosed in autopsy, were earlier clinically undiagnosed [10,11]. Diffuse Large B cell lymphoma is the most common type of NHL (Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma), frequently observed in adults, and so is indolent lymphoma [12]. The mean age range of autopsy confirmation of HLM is about 36-46 years [10,11,13], whereas the age of the deceased was 33 years in the present case.

Lymphoma may be localized, and it may later tend to be rapidly progressive. Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) involves nodal or extranodal sites, including the Waldeyer ring, lung, bone marrow, spleen, liver, and gut, manifesting as a rapidly growing mass [14,15]. Intravascular B Cell Lymphoma (IVBCL), a rare type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, primarily invades blood vessels and presents with neurological or hemophagocytic symptoms depending on the variant [16]. The spectrum of clinical features in lymphoma includes low- grade intermittent fever, nausea, oliguria, anorexia, abdominal pain, weight loss, oedema, pallor, progressive dyspnea, cognitive decline, painless lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly and lactic acidosis [17-24]. Lymphoid malignancy may be further clinically associated with anemia, hypertension, hypothyroidism, paraplegia and multiorgan failure [25,26]. The present case had an antemortem diagnosis of anemia and hypothyroidism. T wave inversion in lead V1-V3 ECG is a normal variant in children but indicates cardiac pathology in adults [27], which does not exclude secondaries or lymphoid infiltration in the present case. In aggressive cases of lymphoma, autopsy may reveal septic and disseminated intravascular coagulation- like picture bone marrow hyperplasia and hepatosplenomegaly [18,19]. The correlation of gross autopsy features with histopathological findings remains crucial for diagnosis, especially in cases with atypical presentations of HLMs [17,18,29].

Generally, painless lymphadenopathy is found in most HLMs [17]. Enlargement of peripancreatic, mesenteric, hilar, paratracheal, paraaortic and mediastinal lymph nodes have been reported [10]. In cases of NHL, diffuse infiltration by tumor cells causes complete architectural effacement. In our case, lymph nodes showed reactive changes, which could be attributed to infection. Tonsils, in HLM, may show monomorphic proliferation of large lymphoid cells, distinct plasmacytoid features, eccentrically placed nuclei, thick nuclear membranes, variably prominent nucleoli, clumped chromatin, and copious pyroninophilic cytoplasm [36]. In the present case, diffuse infiltration of immature lymphoid cells was found in the tonsils.

Diffuse infiltration with angiotropic features, CD20 positivity and decreased ACTH immunoreactivity in the pituitary with associated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism has been reported [37,38]. Diffuse infiltration of lymphoblast cells is found in the pituitary gland with associated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Hatem reported diffuse lymphoid infiltration of skeletal muscle in multiple cores with pseudo-glandular structures and sheets observable in low-power microscopy [39]. Skeletal muscle exhibited immature lymphoblast infiltration, with features like large cells, irregular nuclear contours, vesicular chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and moderate cytoplasm in high-power microscopy.

Thyroid dysgenesis, which includes thyroid agenesis, hypoplasia and ectopic thyroid, amounts to 80-85% of congenital hypothyroidism [40,41]. Acute leukemia is linked to autoimmune thyroid diseases like Graves' and Hashimoto's thyroiditis, with hypothyroidism being a common outcome of thyroid lymphoma [42]. Also, secondary hypothyroidism is most commonly associated with pituitary disorders/abnormalities [43, 44]. A case study by Foresti showed a cause-effect relationship between leukemic infiltration of the thyroid gland and hypothyroidism, with progressive reduction in thyroid hormones and increases in TSH levels [45]. In our case, there was no trace of thyroid in the neck or mediastinum. Clinically, the thyroid profile has shown decreased secretion of thyroid hormone levels, suggesting the possibility of ectopic thyroid. However, no glandular tissue was identifiable or appreciable in the usual reported areas of ectopic thyroid during the autopsy [46]. A mediastinal unidentified tissue excised in an autopsy suspected of ectopic thyroid also did not show any histological components of thyroid tissue; only lymphoid aggregates were found in the background of skeletal muscle cells. This is similar to a study by Waghmare TP et al. where 18% of the NHL cases had soft fleshy yellow-white mass [10].

The thymus showed hyperplasia with a preponderance of immature B cells in our case. Lymphoma may cause thymus enlargement either by primary involvement or secondary infiltration following the invasion of adjacent lymph nodes. Medullary B-cell lymphoma in the thymus is found in 2% of cases with NHL [47]. Malignant lymphoma in the thymus can resemble hyperplastic thymus. Histologically proven invasion in the thymus was not revealed even in advanced imaging methods like FDG or chemical shift MRIs.[48].

Petechial hemorrhages in the ventricular subendocardial region and cardiac hypertrophy were reported in the literature [10, 49]. The tumor cell infiltrates are reported in the myocardium, epicardium, conduction pathway [49,50], cardiac septum and valves [10]. In the present case, the heart displayed petechiae, inflammation with interstitial oedema, lymphoid aggregates, thick aortic and vessel walls, myxoid changes, and enhanced fibrosis.

Pulmonary nodules, mostly calcified and peripheral lung oedema, have been reported [18,19]. Doran reported extensive neoplastic infiltration, generally filling vessels and spilling out into the alveoli while associated with thrombo-embolism and infection (pneumococcus, aspergillus) in the lungs [51]. Microscopic examination of the edematous lung, in our case, revealed dilated alveoli with interstitial congestion with chronic inflammatory cells with bacterial clumps and hemosiderin macrophages.

Reported findings of lymphoma in the liver include neoplastic infiltration, fibrosis, cancerous nodules, necrotic areas, Reed–Sternberg cells, hypocellular regions, diffuse organ filtration by leukemic cells, profound infiltration of CD30 (Ki-1) positive lymphoma cells [11,52,53]. Enlarged hemorrhagic lymph nodes at porta hepatis were also reported by Waghmare TP et al. [10]. Infiltrates in sinusoidal and periportal regions with nodular aggregates were recorded. Liver, in the present case, periportal chronic inflammation with bridging fibrosis, focal interface hepatitis, sinusoidal dilatation with large lymphoid cells, despite normal hepatic architecture.

Hemorrhagic splenic infarcts involve vascular congestion, hemorrhage, and necrosis, while septic infarcts involve acute or chronic inflammatory infiltrates. Lymphoma-induced splenic infarctions result from blood flow interruption and hence bland infarcts are pale, wedge-shaped, and subcapsular. Septic infarcts have suppurative necrosis and large depressed scars during healing. Splenic abscesses show chronic inflammatory infiltrates and necrotic cells [54]. In our case, the spleen was enlarged with massive pale infarcts, implying the possibility of splenic vessel thrombosis. About 10% of splenic infarcts progress to bacterial abscesses in immunocompromised individuals [55,56]. In the present case, there was a progression into a splenic abscess in the hilar region.

Renal enlargement and deposits are reported in HLM [10], while renal pelvic hemorrhage was found in our case. The microscopic findings include acute tubular necrosis, thyroidisation of tubules and focal tubular atrophy with hyaline casts. Tubular atrophy involving broader areas and delineated interstitial fibrosis along the medullary rays forming a striped scarring pattern suggest chronic ischemia. The thyroidization pattern is often seen in urinary reflux or chronic pyelonephritis [57].

Testicular infiltration in leukemia cases is typically bilateral but asymmetric in severity, starting in one testis before affecting both. Specific size measurements of affected testis were hardly found in autopsy-based literature. Its severity is similar to other sites but can be second only to marrow, lymph nodes, and spleen involvement. Microscopic infiltration is most common in acute leukemia, less common in chronic leukemia, and less frequent in lymphoma [58]. Atrophy of the seminiferous tubules with immature lymphoid cells with thickened tunica was observed in our case. Abnormally small testes, smaller than the 50th percentile for age, can be caused by congenital or acquired factors.[59].

Waghmare & Moller reported leukemic infiltrates in the brain parenchyma, meningeal and Virchow robin space [10,60]. Thirunavukkarasu reported patchy myelin pallor in subcortical areas without over-demyelination due to lymphoma cell infiltration [61]. In our case, cerebral vessels were dilated, along with increased vascular and parenchymal lymphocytic infiltrates.

Immunohistochemical studies help to type the tumor cells infiltrating various organs like the lungs, liver, spleen, pituitary gland, ovaries, uterus, and bone marrow. Diffuse large cell B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) tests positive for CD20, CD79a, bcl-2, and MUM1 but negative for CD3, CD5, CD10, CD 56, bcl-6, and cyclin D1 [20, 26]. Reportedly, diffuse CD20 positivity is found in lymphoid cells in sinusoidal and interstitial sites with a Ki-67 index of about 80% to 90% [26]. The CD20 negative subtype of DLBCL is rare and aggressive, with lesser survival rates [62]. B cell lymphoblastic leukemia also tests positive for TdT, CD34, CD79a or PAX5 [63]. IVLBCL exhibits strong intravascular CD20 and CD45 positivity [21]. In the present case, immature B cells in the pituitary, liver and testis tested positive for Tdt, CD34, and CD79a and negative for CD3 and CD20, suggesting B cell lymphoma or leukemia as a final impression on immunohistochemical confirmation. Following flow cytometry, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis is the method of choice for confirmatory diagnosis [64]. CD34 is a transmembrane phosphoglycoprotein found on cell surfaces in humans and animals, used to identify and isolate cancer stem cells (CSC). It is positive in leukemia, breast and lung cancer, and other types of tumors [65]. Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase (Tdt) is a DNA polymerase found in high levels in the thymus, low levels in normal bone marrow, and absent in normal peripheral blood leukocytes. In adult leukemias, the Tdt level is elevated primarily in lymphoblastic leukemia and low in myeloblastic leukemia [66]. CD79, pan B-cell marker, is a dimeric, transmembrane protein, which, along with surface immunoglobulin, is expressed from the pre-B stage to the plasma cell stage of differentiation. It is found in B-cell lymphomas, B-cell lines, most acute leukemias of precursor B-cell type, megakaryocytic lesions and certain myelomas [67].

Hematological malignancies exhibit a dynamic spectrum of infections among the affected patients [68]. Most of the infections were either systemic or pulmonary [69]. Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa were the most frequent organisms isolated, resulting in mortality rates up to 48% in diagnosed cases of HLMs [70]. Escherichia Coli is isolated from blood and fluid culture in the present case, forming the primary foci for septicemia like in other cases [70-73].

The specific subtype of B-cell lymphoma may also influence the primary cause of death [10,74]. The progression and transformation into aggressive subtypes, such as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, has an unfavourable prognosis and increased mortality rates [20]. Complications from the disease, treatment-related side effects and comorbidities contribute to mortality [28, 75-77]. Death was commonly caused by Disseminated malignancy followed by fatal respiratory illness or complications [10,71]. Any infiltrative diseases involving the spleen can also lead to spleen rupture, causing intraperitoneal bleeding, shock, and death [78- 80]. Other causes of death include infection, hemorrhagic shock, hemoperitoneum, thromboembolism, increased intracranial tension with cerebral oedema and conduction abnormalities and associated congenital heart disease [10,20]. Significant autopsy findings in cases of septicemia include pulmonary oedema, diffuse alveolar damage with micro- thrombosis, inflammation & ischemic necrosis of cardiac tissues, acute tubular necrosis, cholestatic jaundice, liver necrosis with sinusoidal aggregates, partial liquefaction of spleen, hemorrhagic adrenal gland, cerebral petechiae, sub-serosal or submucosal hemorrhages in the gastrointestinal tract and features of disseminated intravascular coagulation [81]. In the present case, death is attributed to septicemia secondary to B cell lymphoma in its advanced stage involving multiple organs. Multiple conditions, including syndromic abnormalities like hypogonadism and Kallmann syndrome, were in consideration before concluding the autopsy cause of death in this case. However, the findings from ancillary investigations of the tissues and fluids, in corroboration with the gross features of the case, directed the focus of causality towards B cell lymphoma.

Conclusion

The unexpected discovery of B-cell lymphoma in this 33-year-old man with a history of anemia and hypothyroidism demonstrates th e potential for these conditions to remain undetected until postmortem investigation. The gross findings, extensive lymphoid infiltration observed across multiple organs on microscopy, and immunohistochemical findings provided crucial evidence for diagnosing B-cell lymphoma. Septicemia, the common fatal complication of B-cell lymphoma as in any HLM, had caused death in this case. The case report highlights the importance of comprehensive autopsy examinations in identifying clinically undiagnosed malignancies, particularly HLMs.

Limitations

The spleen and bone marrow were not subjected to microscopic studies using cytomorphology, histomorphology, and immunohistochemistry, thereby posing difficulty in locating the lymphoma's primary origin.

Suggestions

For Autopsy Surgeons: The case highlights the importance of autopsy in medical education, quality assurance, and disease understanding. Postmortem diagnosis of B-cell lymphomas can be challenging due to heterogeneity and limited tissue samples. Understanding gross autopsy findings in HLM is crucial for prompt recognition and management. In unexplained anemia or endocrinological abnormalities, an autopsy should also rule out HLM.

For Clinicians: The case report emphasizes the importance of clinicians detecting underlying malignancies in cases with atypical presentations or unexplained deterioration. Advancements in diagnostic techniques like noncoding RNAs, Next-Generation Sequencing, and radiomics provide new insights into disease pathogenesis and development, while tissue proteomics and digital pathology can enhance early detection [82-86].

Conflicts of interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest in the submitted work.

Funding/services

All authors have declared that no financial support or service was received from any organization for the submitted work.

Ethical Approval & Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with animals. This is a retrospective case report of a medicolegal autopsy. The case data has been completely anonymized with proper de- identification of contents in this report.

References

Hanzlick R, Hunsaker JC, Davis GJ. Guidelines for Manner of Death Classification. Atlanta. GA. National Association of Medical Examiners. 1st ed. 2002. Available online from: Link

Our role in investigating deaths [Internet]. Scotland. Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service. 2023 June 9 [Updated on 2024 July 16. Cited on 14 September 2024]. Available at: Link

Stiles MK, Wilde AA, Abrams DJ, Ackerman MJ, Albert CM, Behr ER, Chugh SS, Cornel MC, Gardner K, Ingles J, James CA. 2020 APHRS/HRS expert consensus statement on the investigation of decedents with sudden unexplained death and patients with sudden cardiac arrest, and of their families. Heart rhythm. 2021. 18(1). e1-e50. Link

Bundock EA, Eason EA, Andrew TA, Knight LD, Lear KC, Sens MA, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Warner M. Death certification and surveillance. Unexplained Pediatric Deaths: Investigation, Certification, and Family Needs [Internet]. 2019. Accessed at Link

Rathva VK, Bhoot RR. Assessment of Sudden Natural Deaths in Medico-Legal Autopsies at Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital. Indian J Forensic Med Toxicol. 2023;17(4). 25-29. Link

Parmar PB, Rathod GB, Bansal P, Yadukul S, Bansal AK. Utility of inquest and medico-legal autopsy in community deaths at tertiary care hospital of India. J. Family Med. Prim. Care. 2022;11(5):2090-3. Link

Tirpude B, Nagrale N, Murkey P, Zopate P, Patond S. Medicolegal profile of brought dead cases received at mortuary. J For Med Sci Law. 2012. 21(2). 2192. Available online from - Link

Parajuli S, Aneja A, Mukherjee A. Undiagnosed fatal malignancy in adult autopsies: a 10-year retrospective study. Hum. Pathol. 2016;48:32-6. Link

Javed N, Rueckert J, Mount S. Undiagnosed Malignancy and Therapeutic Complications in Oncology Patients: A 10-Year Review of Autopsy Cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2022;146(1):101-6. Link

Waghmare TP, Prabhat DP, Keshan P, Vaideeswar P. An autopsy study of hematolymphoid malignancies. Int J Res Med Sci. 2019 Apr;7(4):1079. Link

Dierksen J, Buja LM, Chen L. Clinicopathologic findings of hematological malignancy: A retrospective autopsy study. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci.. 2015 ;45(5):565-73.

Saraf SR, Naphade NS, Kalgutkar AD. An autopsy study of misdiagnosed Hemato-lymphoid disorders. Indian J Pathol Oncol. 2016;3(2):182-6. Link

Xavier ACG, Siqueira SAC, Costa LJM, Mauad T, Saldiva PHN. Missed diagnosis in hematological patients-an autopsy study. Virchows Arch.2005;446:225-31. Link

Cho JS, Lee KR, Kim BS, Choi GM, Lee JS, Huh JS, Jang B. Multifocal extranodal involvement in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): bone, soft tissue, testis, and kidney. Investig. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2022;26(1):48-54. Link

De Leval L, Bonnet C, Copie-Bergman C, Seidel L, Baia M, Brière J, Molina TJ, Fabiani B, Petrella T, Bosq J, Gisselbrecht C. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of Waldeyer's ring has distinct clinicopathologic features: a GELA study. Ann. Oncol. 2012;23(12):3143-51. Link

Breakell T, Waibel H, Schliep S, Ferstl B, Erdmann M, Berking C, Heppt MV. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a review with a focus on the prognostic value of skin involvement. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(5):2909-19. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29050237

Mosunjac MB, Sundstrom B, Mosunjac MI. Unusual presentation of anaplastic large cell lymphoma with clinical course mimicking fever of unknown origin and sepsis: autopsy study of five cases. Croat Med J. 2008;49(5):660-8. https://doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2008.5.660

Lo CH, Cheng SY. An autopsy case report of sudden collapse: Diffuse large B cell lymphoma with predominant intravascular distribution and bone marrow involvement. J Case Rep Images Pathol. 2021.7. 10.5348/100053Z11CO2021CR. Available online from: https://www.ijcripathology.com/archive/abstract/100053Z11CO2021

Fiegl M, Greil R, Pechlaner C, Krugmann J, Dirnhofer S. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma with a fulminant clinical course: a case report with definite diagnosis post mortem. Ann. Oncol. 2002;13(9):1503-6. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdf214

Kubo K, Kimura N, Mabe K, Matsuda S, Tsuda M, Kato M. Acute liver failure associated with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: an autopsy case report. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2020;13:1213-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-019-01091-6

Maiese A, La Russa R, De Matteis A, Frati P, Fineschi V. Post-mortem diagnosis of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(6):1-5 https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060520924262

Eyerer F, Gardner JA, Devitt KA. Mantle cell lymphoma presenting with lethal atraumatic splenic rupture. Autops Case Rep. 2021;11:e2021340. https://doi.org/10.4322/acr.2021.340

Masterman D, Gandhi S, Singh A, Singh T, Kaur A. A Fatal Etiology of Splenic Infarction. J. Community Hosp. Intern. Med. Perspect. 2022;12(5):78. https://doi.org/10.55729/2000-9666.1097

Moen M, Hamilton-Dutoit S, Steiniche T, Gude MF. . B-cell hepatosplenic lymphoma presenting in adult patient after spontaneous splenic rupture followed by severe persistent hypoglycaemia: type B lactic acidosis and acute liver failure. BMJ Case Rep. 2023. 16(12). e257154. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2023-257154

Emanuel AJ, Presnell SE. Acute kidney injury and cardiac arrhythmia as the presenting features of widespread diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Autops Case Rep. 2019;9(3). https://doi.org/10.4322/acr.2019.114

Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC. Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Systems. Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. 9th Ed. Elsevier Saunders. 2013. 429-443.

Aro AL, Anttonen O, Tikkanen JT, Junttila MJ, Kerola T, Rissanen HA, Reunanen A, Huikuri HV. Prevalence and prognostic significance of T-wave inversions in right precordial leads of a 12-lead electrocardiogram in the middle-aged subjects. Circ Res. 2012;125(21):2572-7. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.112.098681

Delgado J, Nadeu F, Colomer D, Campo E. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: from molecular pathogenesis to novel therapeutic strategies. Haematologica. 2020;105(9):2205. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2019.236000

Karstensen KT, Schein A, Petri A, Bøgsted M, Dybkær K, Uchida S, Kauppinen S. Long non-coding RNAs in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Non-coding RNA. 2020;7(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/ncrna7010001

Zucker S. Anemia in cancer. Cancer Investigation. 1985 Jan 1;3(3):249-60. https://doi.org/10.3109/07357908509039786

Yasmeen T, Ali J, Khan K, Siddiqui N. Frequency and causes of anemia in Lymphoma patients. Pak. J. Med. 2019;35(1):61. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.35.1.91

Ghosh J, Singh RK, Saxena R, Gupta R, Vivekanandan S, Sreenivas V, Raina V, Sharma A, Kumar L. Prevalence and aetiology of anemia in lymphoid malignancies. Natl Med J India. 2013;26(2):79-81.

Morrow TJ, Volpe S, Gupta S, Tannous RE, Fridman M. Anemia of cancer in intermediate-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. South Med J-. 2002;95(8):889-96. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007611-200295080-00021

Bohlius J, Weingart O, Trelle S, Engert A. Cancer-related anemia and recombinant human erythropoietin—an updated overview. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2006;3(3):152-64. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncponc0451

Szczepanek-Parulska E, Hernik A, Ruchała M. Anemia in thyroid diseases. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2017;127(5):352-60. https://doi.org/10.20452/pamw.3985

Barton JH, Osborne BM, Butler JJ, Meoz RT, Kong J, Fuller LM, Sullivan JA. Non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma of the tonsil. A clinicopathologic study of 65 cases. Cancer. 1984;53(1):86-95. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19840101)53:1<86::aid-cncr2820530116>3.0.co;2-e

Kenchaiah M, Hyer SL. Diffuse large B-cell non Hodgkin's lymphoma in a 65-year-old woman presenting with hypopituitarism and recovering after chemotherapy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:1-4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-5-498

Mathiasen RA, Jarrahy R, Tae Cha S, Kovacs K, Herman VS, Ginsberg E, Shahinian HK. Pituitary lymphoma: a case report and literature review. Pituitary. 2000;2:283-7. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1009969417380

Hatem J, Bogusz AM. An Unusual Case of Extranodal Diffuse Large B‐Cell Lymphoma Infiltrating Skeletal Muscle: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Pathol. 2016;2016(1):9104839. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/9104839

Rastogi MV, LaFranchi SH. Congenital hypothyroidism. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2010;5:1-22. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-5-17

Alam A, Ashraf H, Khan K, Ahmed A. Uncovering Congenital Hypothyroidism in Adulthood: A Case Study Emphasizing the Urgency of Screening and Clinical Awareness. Cureus. 2023;15(9). https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.45611

Moskowitz C, Dutcher JP, Wiernik PH. Association of thyroid disease with acute leukemia. Am. J. Hematol. 1992;39(2):102-7. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.2830390206

Vaillant PF, Devalckeneer A, Csanyi-Bastien M, Ares GS, Marks C, Mallea M, Cortet-Rudelli C, Maurage CA, Aboukaïs R. An unusual ectopic thyroid tissue location & review of literature. Neurochirurgie. 2023;69(6):101497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuchi.2023.101497

Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, Hennessey JV, Klein I, Mechanick JI, Pessah-Pollack R, Singer PA, Woeber KA. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults. the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Thyroid Association Taskforce on Hypothyroidism in Adults. Endocr Pract. 2012. 22(12).1200-1235. https://doi.org/10.4158/ep12280.gl

Foresti V, Parisio E, Scolari N, Ungaro A, Villa A, Confalonieri F. Primary hypothyroidism due to leukemic infiltration of the thyroid gland.J. Endocrinol. Invest. 1988;11:43-5.

Santangelo G, Pellino G, De Falco N, Colella G, D'Amato S, Maglione GM, De Luca R, Canonico S, De Falco M. Prevalence, diagnosis and management of ectopic thyroid glands. Int J Surgery. 2016;28:S1-6.

Hakim A, Sather C, Naik T, McKenna Jr RJ, Kamangar N. Masses of The Anterior Mediastinum. Medical Management of the Thoracic Surgery Patient. 2009;32:365. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-1-4160-3993-8.00042-8

Takahashi K, Inaoka T, Murakami N, Hirota H, Iwata K, Nagasawa K, Yamada T, Mineta M, Aburano T. Characterization of the normal and hyperplastic thymus on chemical-shift MR imaging. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2003;180(5):1265-9. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.180.5.1801265

Johnson CD. Heart Block in Leukemia and Lymphoma. ClinProg Pacing Electrophysiol.1984;2:539-46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8167.1984.tb01675.x

Wiernik PH, Sutherland JC, Stechmiller BK, Wolff J. Clinically significant cardiac infiltration in acute leukemia, lymphocytic lymphoma, and plasma cell myeloma. Med Pediat Oncol.1976;2:75-85. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpo.2950020109

Doran HM, Sheppard MN, Collins PW, Jones L, Newland AC, WALT JV. Pathology of the lung in leukemia and lymphoma: a study of 87 autopsies. Histopathology. 1991;18(3):211-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2559.1991.tb00828.x

Dourakis SP, Tzemanakis E, Deutsch M, Kafiri G, Hadziyannis SJ. Fulminant hepatic failure as a presenting paraneoplastic manifestation of Hodgkin's disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11(9):1055-8. https://doi.org/10.1097/00042737-199909000-00019

Scheimberg IB, Pollock DJ, Collins PW, Doran HM, Newland AC, Walt JV. Pathology of the liver in leukemia and lymphoma. A study of 110 autopsies. Histopathology. 1995;26(4):311-21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2559.1995.tb00192.x

Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC. Embolism. Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. 9th Ed. Elsevier Saunders. 2013.92.

Wadsworth PA, Miranda RN, Bhakta P, Bhargava P, Weaver D, Dong J, Ovechko V, Norman M, Muthukumarana PV, Bayes MG, Mallick J. Primary splenic diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma presenting as a splenic abscess. E J Haem. 2023;4(1):226-31. https://doi.org/10.1002/jha2.642

O'keefe JR JH, Holmes JR DR, Schaff HV, Sheedy II PF, Edwards WD. Thromboembolic splenic infarction. Elsevier InMayo Clinic Proceedings 1986;61(12).967-972. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62638-x

Fogo AB. AJKD atlas of renal pathology: tubular atrophy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67(6):e33-4. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.04.007

Givler RL. Testicular involvement in leukemia and lymphoma. Cancer. 1969;23(6):1290-5.

Yang DM, Choi HI, Kim HC, Kim SW, Moon SK, Lim JW. Small testes: clinical characteristics and ultrasonographic findings. Ultrasonography. 2021;40(3):455. https://doi.org/10.14366/usg.20133

Bojsen‐Moller M, Nielsen JL. CNS involvement in leukemia: an autopsy study of 100 consecutive patients. Acta Pathologica Microbiologica Scandinavica Series A: Pathology. 1983;91(1‐6):209-16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1699-0463.1983.tb02748.x

Thirunavukkarasu B, Gupta K, Shree R, Prabhakar A, Kapila AT, Lal V, Radotra B. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the CNS, with a “Lymphomatosis cerebri” pattern. Autopsy Case Rep. 2021;11:e2021250. https://doi.org/10.4322/acr.2021.250

Castillo JJ, Chavez JC, Hernandez-Ilizaliturri FJ, Montes-Moreno S. CD20-negative diffuse large B-cell lymphomas: biology and emerging therapeutic options. Expert Rev. Hematol.. 2015;8(3):343-54. https://doi.org/10.1586/17474086.2015.1007862

Kim JY, Om SY, Shin SJ, Kim JE, Yoon DH, Suh C. Case series of precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma. Blood Res. 2014;49(4):270-4. ttps://doi.org/10.5045/br.2014.49.4.270

Ventura RA, Martin-Subero JI, Jones M, McParland J, Gesk S, Mason DY, Siebert R. FISH analysis for the detection of lymphoma-associated chromosomal abnormalities in routine paraffin-embedded tissue. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8(2):141-51. https://doi.org/10.2353/jmoldx.2006.050083

Radu P, Zurzu M, Paic V, Bratucu M, Garofil D, Tigora A, Georgescu V, Prunoiu V, Pasnicu C, Popa F, Surlin P. CD34—Structure, functions and relationship with cancer stem cells. Medicina. 2023;59(5):938. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59050938

Gordon DS, Hutton JJ, Smalley RV, Meyer LM, Vogler WR. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT), cytochemistry, and membrane receptors in adult acute leukemia. Blood. 1978 ;52(6):1079-88. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.v52.6.1079.bloodjournal5261079

Martin AW. Immunohistology of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. In: Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry. WB Saunders .2011: 156-188. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-1-4160-5766-6.00010-8

Srivastava VM, Krishnaswami H, Srivastava A, Dennison D, Chandy M. Infections in haematological malignancies: an autopsy study of 72 cases. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1996;90(4):406-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0035-9203(96)90524-6

Chandran R, Hakki M, Spurgeon S. Infections in leukemia. Sepsis-an ongoing and significant challenge. 2012:334-68. https://doi.org/10.5772/50193

Guentzel MN. Escherichia, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Serratia, Citrobacter, and Proteus. Medical Microbiology. 4th edition. 1996. https://doi.org/10.1128/9781555816728.ch37

Rolston KV. Infections in patients with acute leukemia. Infections in hematology. 2015:3-23. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-44000-1_1

Yin X, Hu X, Tong H, You L. Trends in mortality from infection among patients with hematologic malignancies: differences according to hematologic malignancy subtype. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2023;14. https://doi.org/10.1177/20406223231173891

Nørgaard M. Risk of infections in adult patients with haematological malignancies. The Open Infectious Diseases Journal. 2012 Oct 2;6(1):46-51. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874279301206010046

Pimenta FM, Palma SM, Constantino-Silva RN, Grumach AS. Hypogammaglobulinemia: a diagnosis that must not be overlooked. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2019 Oct 10;52:e8926. https://doi.org/10.1590/1414-431x20198926

Santos ES, Raez LE, Salvatierra J, Morgensztern D, Shanmugan N, Neff GW. Primary hepatic non-Hodgkin's lymphomas: case report and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(12):2789-93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08766.x

Lorigan P, Radford J, Howell A, Thatcher N. Lung cancer after treatment for Hodgkin's lymphoma: a systematic review. Lancet oncol. 2005;6(10):773-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(05)70387-9

Mei M, Wang Y, Song W, Zhang M. Primary Causes of Death in Patients with Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Cancer Manag Res. 2020:3155-62. https://doi.org/10.2147/cmar.s243672

Whimbey E, Kiehn TE, Brannon P, Blevins A, Armstrong D. Bacteremia and fungemia in patients with neoplastic disease. Am J. Med. 1987;82(4):723-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(87)90007-6

Amin Z, Freeman SJ. Pancreas and Spleen. Clinical Ultrasound, 2-Volume Set E-Book: Expert Consult: Online and Print. 2011:283. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-7020-3131-1.00017-1

Ahbala T, Rabbani K, Louzi A, Finech B. Spontaneous splenic rupture: case report and review of literature. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37(1). https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2024.48.190.43645

Stassi C, Mondello C, Baldino G, Ventura Spagnolo E. Post-mortem investigations for the diagnosis of sepsis: a review of literature. Diagnostics. 2020;10(10):849. http://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics10100849.

Scott DW, Wright GW, Williams PM, et al. Determining Cell-of-Origin Subtypes of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Using Gene Expression in Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Tissue. Blood. 2014;123(8):1214-7. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-11-536433

Lawrie CH, Gal S, Dunlop HM, Pushkaran B, Liggins AP, Pulford K, Banham AH, Pezzella F, Boultwood J, Wainscoat JS, Hatton CS. Detection of elevated levels of tumor‐associated microRNAs in serum of patients with diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008;141(5):672-5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07077.x

Gillies RJ, Kinahan PE, Hricak H. Radiomics: images are more than pictures, they are data. Radiology. 2016;278(2):563-77. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2015151169

Griffin J, Treanor D. Digital pathology in clinical use: where are we now and what is holding us back? Histopathology. 2017;70(1):134-45. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.12993

Zheng GX, Terry JM, Belgrader P, Ryvkin P, Bent ZW, Wilson R, Ziraldo SB, Wheeler TD, McDermott GP, Zhu J, Gregory MT. Massively parallel digital transcriptional profiling of single cells. Nat commun. 2017;8(1):14049. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14049

*Corresponding author and requests for clarifications and further details:

Dr Mukesh R,

Assistant Professor, Department of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology,JIPMER, Pondicherry.

Mail at: mukeshfmt22@gmail.com